American historians use several different nomenclatures to designate various immigration waves to the United States. The immigration during the period between 1820 and 1880 is often called “Old Immigration” ((RACE AND ETHNIC RELATIONS: AMERICAN AND GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES, Cengage Learning, 2008; ISBN: 0-495-50436-X. pp. 117 -8)). Prominent among this wave were Jewish immigrants from Bavaria ((Hasia R. Diner. The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000. Univ. of California Press 2004; ISBN: 0-520-24848-I. p83)). There were both ‘pull’ and ‘push’ reasons for people to undertake such a perilous and gruelling journey. In this essay, I will attempt to demonstrate that for Bavarian Jews in the first half of the 19th century, the ‘push’ motivation was pre-eminent. Jews left Bavaria for endemic reasons, such as antisemitism and poor economic prospects as well as for structural reasons – the Bavarian Jews’ Edict of 1813 ((James F. Harris. The people speak!: anti-Semitism and emancipation in nineteenth-century Bavaria. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1994; ISBN: 0-472-10437-3. pp209-37 & 241-45)).

Given the state of administration and technology in 19th century United States, immigration statistics have to be taken with a large grain of salt. Never the less, official figures show two peaks in the rate of German immigration: the first for the period 1841 – 1860, the second for 1881 – 1900 ((US Dept. of Justice. 2001 Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Table 2.)). But these official statistics don’t allow us to single out Bavarian Jews.

Using data extracted from the Jewish ‘Family Book’ from one little Bavarian-Swabian town – Altenstadt, I will illustrate the temporal course of this immigration wave. Civil records for 19th century German Jews consisted essentially of birth, marriage and death records, as well as the so calle ‘Familienbuch’, a registry of Jewish families living (legitimately) in the community. For each family the house or house section is listed; for the head of household and dependents the names, dates of birth, sometimes dates of marriage and deaths are listed as well. The Altenstadt family book was maintained by the rabbi, as manifest by occasional Hebrew dates of birth.

Between 1800 and 1869 Altenstadt had three rabbis. Abraham Mayer, born about 1767, died in 1837. He was followed by his son Mayer (Meir) Mayer, born 1796 who died in March 1849. Both Abraham and his son Mayer were born in Altenstadt and lived there most of their lives. After Mayer’s death there was an interregnum with rabbis from neighbouring communities pinch hitting. In 1853 Emanuel Schwab, born 1812 in Heidingsfeld near Würzburg took over the position, acting also as school principal. After Schwab’s death in July 1869 the Jewish community of Altenstadt had shrunk to the point, where it no longer warranted its own rabbi. The Altenstadt family book was started after Abraham Mayer’s death, for he doesn’t feature in it. His son Mayer, though, was totally familiar with the community, having grown up in it and knowing everybody. It is likely from the entries that both he and Emanuel Schwab were the authors of the family book.

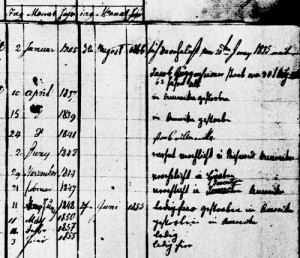

The rabbis noted important features and events for each family and individual in the last column. Showing a full page of the family book would tax the layout capability of a blog. I have, therefore, selected an illustrative excerpt, exposing just the last few columns of a page including dates of birth and comments for the family of Jacob Koppel Guggenheimer, a farmer and horse dealer, and his wife Jette Monheimer. It becomes obvious, how many of Altenstadt’s Jewish denizens undertook the journey to ‘Amerika’. Sometimes, it was just one or two family members, sometimes it involved whole families.

The rabbis noted important features and events for each family and individual in the last column. Showing a full page of the family book would tax the layout capability of a blog. I have, therefore, selected an illustrative excerpt, exposing just the last few columns of a page including dates of birth and comments for the family of Jacob Koppel Guggenheimer, a farmer and horse dealer, and his wife Jette Monheimer. It becomes obvious, how many of Altenstadt’s Jewish denizens undertook the journey to ‘Amerika’. Sometimes, it was just one or two family members, sometimes it involved whole families.

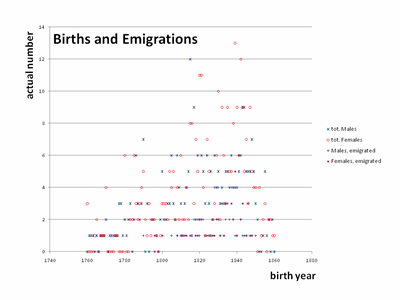

Plotting the actual number of live births and people emigrating according to gender and birth year results in a rather confusing picture. Actual numbers, according to the laws of statistics, are too small to provide a coherent picture. Statistical techniques have to be employed to create some clarity. The first step is to calculate summary statistics:

Plotting the actual number of live births and people emigrating according to gender and birth year results in a rather confusing picture. Actual numbers, according to the laws of statistics, are too small to provide a coherent picture. Statistical techniques have to be employed to create some clarity. The first step is to calculate summary statistics:

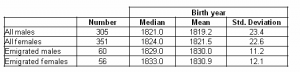

The table shows that more women survived than men. People, who emigrated, were considerably younger than the population in general and emigrating females were slightly younger than males.

The table shows that more women survived than men. People, who emigrated, were considerably younger than the population in general and emigrating females were slightly younger than males.

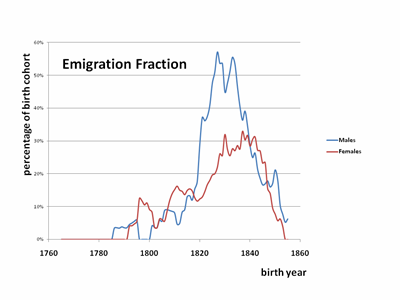

The situation becomes only obvious, after we calculate running averages over a period of ten years, centered at an index year and form the percentage of emigrating individuals to total individuals for each index birth year and gender. We now see that emigration involved a relatively narrow birth cohort, namely people born between 1820 and 1850. At its peak, almost 60% of males and 30% of females emigrated to America. By 1861 the Bavarian Jews’ Edict was repealed. Shortly afterwards, Jews were free to move into cities and to earn their livelihood as they saw fit. The ‘push’ component in the motivation to emigrate had disappeared.

The situation becomes only obvious, after we calculate running averages over a period of ten years, centered at an index year and form the percentage of emigrating individuals to total individuals for each index birth year and gender. We now see that emigration involved a relatively narrow birth cohort, namely people born between 1820 and 1850. At its peak, almost 60% of males and 30% of females emigrated to America. By 1861 the Bavarian Jews’ Edict was repealed. Shortly afterwards, Jews were free to move into cities and to earn their livelihood as they saw fit. The ‘push’ component in the motivation to emigrate had disappeared.

Maybe it is appropriate to sound some methodological caveats. Altenstadt is but one of many small and midsized Jewish communities in Bavaria. It would be unwise to extrapolate the model uncritically to all of Bavaria or even Germany. With the repeal of the Jews’ Edict in 1861, the requirement to keep a family book for the Jewish community ceased, and consequently, the records were no longer updated. This might make the trailing edge of the emigration wave appear more precipitous than it actually was. Never the less, the emigration spike of Bavarian Jews is striking and of interest to many American genealogists with Jewish ancestors in Bavaria.

This blog is quickly becoming a valuable resource. Neat stuff.

A small recommendation would be that you consider uploading larger graph images, but just insert them into the body in a smaller format. That should allow those readers who are interested to access more legible versions. In particular, I would like to see larger versions of the Birth and Emigrations and the Emigration Fraction graphs. The latter is almost legible, but the first isn’t at all.

When will you go ‘live’?

Just beginning to search this out. Got curious after doing some work on ancestry.com.

Great site! This site has been very helpful in my quest of my Altenstadt ancestors who immigrated to Richmond, Virginia in mid 1800’s. Thank you!

Hello,I enjoyed your blog! Before my grandmother passed away in 1996 at the age of 85.she told me her grandparents were German Jews and in her words,”came to America on a cattle boat to escape persecution.” Their names were Elizabeth Heidleberg and John Bickler .They changed the name to Bueglar,to sound less Jewish,when they settled in America. I recently went on Ancestry.com and found a match,saying they came from Bavaria.So,after reading your blog,I’m thinking they were part of this migaration from Bavaria from 1841-1855. THeir son,John Jacob Bueglar was my great-grandfather. He was married to an Irish girl,Mary Clydie Haney. They lived in Kentucky,then Ohio,where my grandmother Esther Bueglar was born. I would appreciate any info! Thank you and God bless!

This is very interesting!

I am taking a family history/genealogy certificate class at the University of Washington and am writing two papers on my great great grandfather Maier Zunder who strongly fits the profile for Bavarian immigration. He was born in 1829 in Fuerth, emigrated in 1848. He moved to New Haven and had a long successful career as a merchant, bank president and member of the Board of Education.

How did you get the family book? Did it come from the archives in Munich??

I would love to correspond with you on this.

Sandy Barnes

sandy@dsbarnes.com

Hello, This is a very old post but I found it because Jacob Koppel Guggenheimer was my great, great, great grandfather. I am trying to confirm his birth and death dates and whether he is buried in Laupheim. Does the page you have above have any information that would be helpful?