Together with a German friend my wife and I are just completing a book documenting the features and history of an old Jewish cemetery in rural Bavarian Swabia (see the picture above). During our work we becam increasingly aware of the fact that many tombstones which should be there, are actually nowhere. This blog explores the mystery of the missing tombstones.

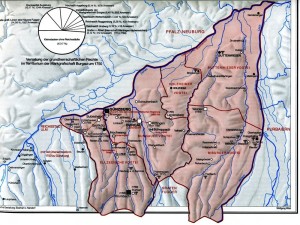

Krumbach is a small market town in Southern Germany. In fact, today’s town of Krumbach resulted from the amalgamation of two earlier, separate communities: Krumbach and Hürben. Hürben was a small farming village where Jews had settled since the 16th century. The exact date Jews first put down their roots is somewhat clouded by the mist of history. Although a document from 1759 refers to 1504 ((1759 Urbarium of Hürben)), the first documented, contemporary mention of Jews in Hürben appeared in 1542 ((Imperial Proclamation of the Freedom of the City of Memmingen, 1542.)). The first legal resident Jew – Salomon Jud – was recorded in 1580 ((1580 Urbarium of Hürben)). A single named legal person probably encompassed a whole household including any number of children, inlaws and assorted helpers.

A Hürben rabbi Moses from Angelberg is mentioned in 1568 and rabbi Isak of Prerau appears in 1670. It is likely that, over the years, Jews migrated to Hürben in groups from other communities, but this is documented only for the Jews evicted from Thannhausen in 1718. By 1759 at least eight extended Jewish families were living in Hürben, but only two owned their own houses.

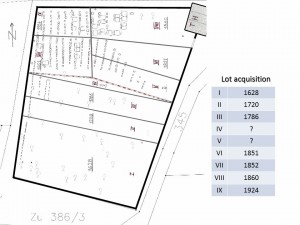

Originally, Jews had to bury their dead in the only Jewish cemetery in the region, near the town of Burgau, the capital of the margraviate bearing the same name, some 16 miles north of Hürben. But in 1628 the Jews of Hürben received permission to establish their own cemetery. In 1675 the Jews were also allowed to build a synagogue, which was subsequently enlarged in 1710 and 1765 to keep pace with an ever growing community. It was rebuilt in 1819 and, finally, destroyed in the Night of Broken Glass – November 9. 1938.

The cemetery, too, was expanded about eight times between 1628 and 1924. Whereas the first Hürben Jews earned their livelihood as pedlars, horse traders, money lenders, wheelers and dealers, over the years they gradually entered settled trades, respected businesses and the professions. The Jewish community of Hürben reached its peak between 1840 and 1850 counting some 652 members.

After 1850 the Jewish population gradually declined, initially due to emigration to North-America, and after 1860, migration to the large urban centers in Germany. The last fourteen Hürben Jews were deported and murdered 1942 in Piaski near Lublin, German occupied Poland.

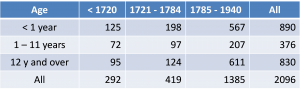

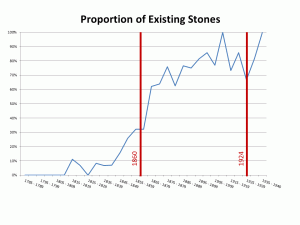

Vital data extracted from a variety of sources allows us to estimate the total number of deaths. Prior to 1784 data derives from burial tax receipts in the archives. From 1785 to 1876 we have analysed the death records contained in the Gatermann films, and death records after 1876 are kept in the municipal archives of Krumbach. Over the duration of Hürben’s Jewish community, approximately 2096 people had died. But 890 of them were children under the age of 1 year. According to Jewish law, children who died within their first 30 days of life warrant very limited obsequies. But given the high infant mortality, the impecunity of most Jews at the time and the cost of stones, few of the very young children would have been given a tombstone.This would lead us to expect at least 1206 graves. But only 231 graves still exist today, none older than 200 years. How have the other, almost thousand tombstones disappeared? The answer to this riddle evolves in stages.

It may not be widely known, but in contrast to the custom in Christian cemeteries, Jewish tombstones are placed for perpetuity. In fact, any unwarranted interference with a grave is strictly prohibited by religious laws. It is thus unthinkable that the headstones were removed by the Jews themselves. Furthermore, there was no need for it. The periodic purchases of land for cemetery expansion show that the size of the cemetery kept pace with the growing number of graves.

In May 1926 Isidor Kahn, retired school principal in Krumbach published a little article in the Journal of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria regarding the history of Jewish Hürben ((Kahn I. Geschichtliches von Hürben-Krumbach. Bayerische Israelitische Gemeindezeitung 1926(5): 139-40.)). In one sentence he deplores the disappearance of the tombstones originating from before the Napoleonic Wars. His explanation, unfortunately, does not hold water. He claimed that all those markers had been carved in oak and were used by the Austrian troops as firewood. While it is true that occasional oaken tomb markers existed at the time, they were by far the minority in Bavaria. Even before 1800, most Jewish tombs were marked by proper headstones. However, he clearly dates the disappearance of the 17th and 18th century stones long before the second World War. It is quite likely that those stones vanished during the Napoleonic Wars for whatever reason. But the event was not recorded in municipal archives.

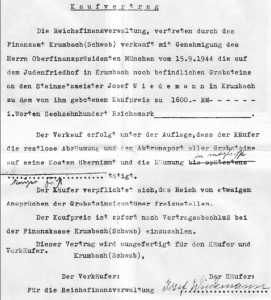

Not much is known about the history of the cemetery during the Nazi period. Pictures taken by the town of Krumbach in 1943 show the cemetery in disarray. We can still recognize some stones which no longer exist today. On September 15. 1944 the Nazi authorities entered a contract with the local master stonemason Joseph Wiedemann, selling him the Jewish cemetery with all its content for 1600.- Reichsmark. The agreement is of interest in several respects: (i) the date – in the fall of 1944 the Allied troops stood at the German border and the end of the Thousand Year Empire was in sight. (ii) the contract required Mr. Wiedemann “to complete the removal of all remaining stones.” In other words, the larceny had been going on long before September 1944, and, (iii) transferring any liability for future claims of loss or damage onto Mr. Wiedemann. In 1989, 45 years later, the son of Joseph Wiedemann received his money back from the Jewish Community in Augsburg.

It is fairly obvious that Joseph Wiedemann bears no guilt in the destruction of the cemetery. In fact, he probably contributed to the preservation of the remaining stones. If he had been involved in their earlier removal, he would have shunned any liability for their damage and disappearance. Furthermore, among the remaining stones there are some big, polished granite blocks, that would have been much more appealing for re-use than the old sandstones that form the bulk of the loss. However, material from other Jewish cemeteries had been ‘recycled’ quite shamelessly.

At the end of the war the remaining stones were lying helter-skelter all over the newest section of the cemetery. They were reset in a rather arbitrary order during the American occupation. It had namely been the custom in 17th and 18th century Jewish cemeteries in Southern Germany for men, women, women having died in child-birth and children, all to be buried in separate rows ((Kuhn P. et al. Jüdischer Friedhof von Georgensgmünd. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich 2006)) ((Judenfriedhof Endingen-Lengnau. Menes Verlag 1993)) ((Bamberger N.B-G. Der jüdische Friedhof von Schmieheim. Bamberger Familien Archiv, Jerusalem 1999)). This order was no longer apparent.

The pattern of tombstone disappearance is very peculiar. There is not a sharp cut-off, but a gradual trend. In fact, the larger, the newer and the more to the north side of the cemetery a grave, the less likely was its tombstone to disappear.

In summary then:

- The 17th and 18th century tombstones went already missing during the Napoleonic Wars.

- Three quarters of the 19th and 20th century tombstones have disappeared gradually between 1938 and 1944.

- It involved mainly the older, smaller sandstones rather than the bigger, newer and flashier granites.

- We conclude that the stones had been removed piecemeal as building material and for foundations, rather than for re-use as gentile headstones.

In retrospect, it is almost impossible to identify existing Krumbach buildings resting on Jewish foundations.

This investigation would not have succeeded without the overwhelming enthusiasm, energy, patience and proficiency of our friend Erwin Bosch, a prominent native of Krumbach. He spent many hundreds, if not thousands of hours in local archives, sifting through dusty documents from five centuries, reading and organising them in order to gradually develop a plausible picture. We are deeply in his debt for his having made our concern his own.

Hello,

I just discovered your blog through the Bavarian Gen site. That Gen site has been a blessing to me as I was able to locate my family records in Altenstadt! I soon discovered that some of my ancestors are buried in the Hebrew cemetery located only one hour from me in Virginia! I didn’t know how to contact you privately but was wondering if you might assist me in solving a genealogy mystery in the records that I have. If not, would you be able to refer to me to a researcher in Altenstadt? There doesn’t seem to be a researcher on the genealogy site that is working on the Rosenheim family.

Also, would you mind if I copy your blog post about the missing headstones? Oh, what I would give to know where my family is buried.

Feel free to contact me directly. Thank you!